The interesting thing about tool calling isn't that AI can use tools. It's that once a system can call tools, it can create loops. And once it can create loops, it can operate without constant human redirection. The path from "AI as assistant" to "AI as autonomous agent" isn't a conceptual leap. It's a series of small technical capabilities that accumulate until the system can run on its own.

We're watching this happen now, and most people aren't noticing the significance.

Start with the trajectory. The internet era gave us software tools, systems humans operated. SaaS made those tools more accessible but didn't change the fundamental relationship: human decides, software executes.

The AI tools era, which started with ChatGPT and similar systems, introduced generation and prediction but kept the same structure. AI suggests, human accepts or rejects. The system can't do anything without a prompt, and it stops after each response waiting for the next one.

AI agents changed the granularity. By "agent," I mean a system that can break down a goal into steps, execute those steps, and handle errors without returning to the human after each action. The human still provides the goal and checks the final output, but the execution path is the agent's domain.

This is closer to delegating than to using a tool. You don't tell the agent which API to call or which error-handling strategy to use. You say "book a meeting with these constraints," and it figures out the steps.

What makes this possible technically? Three things converging:

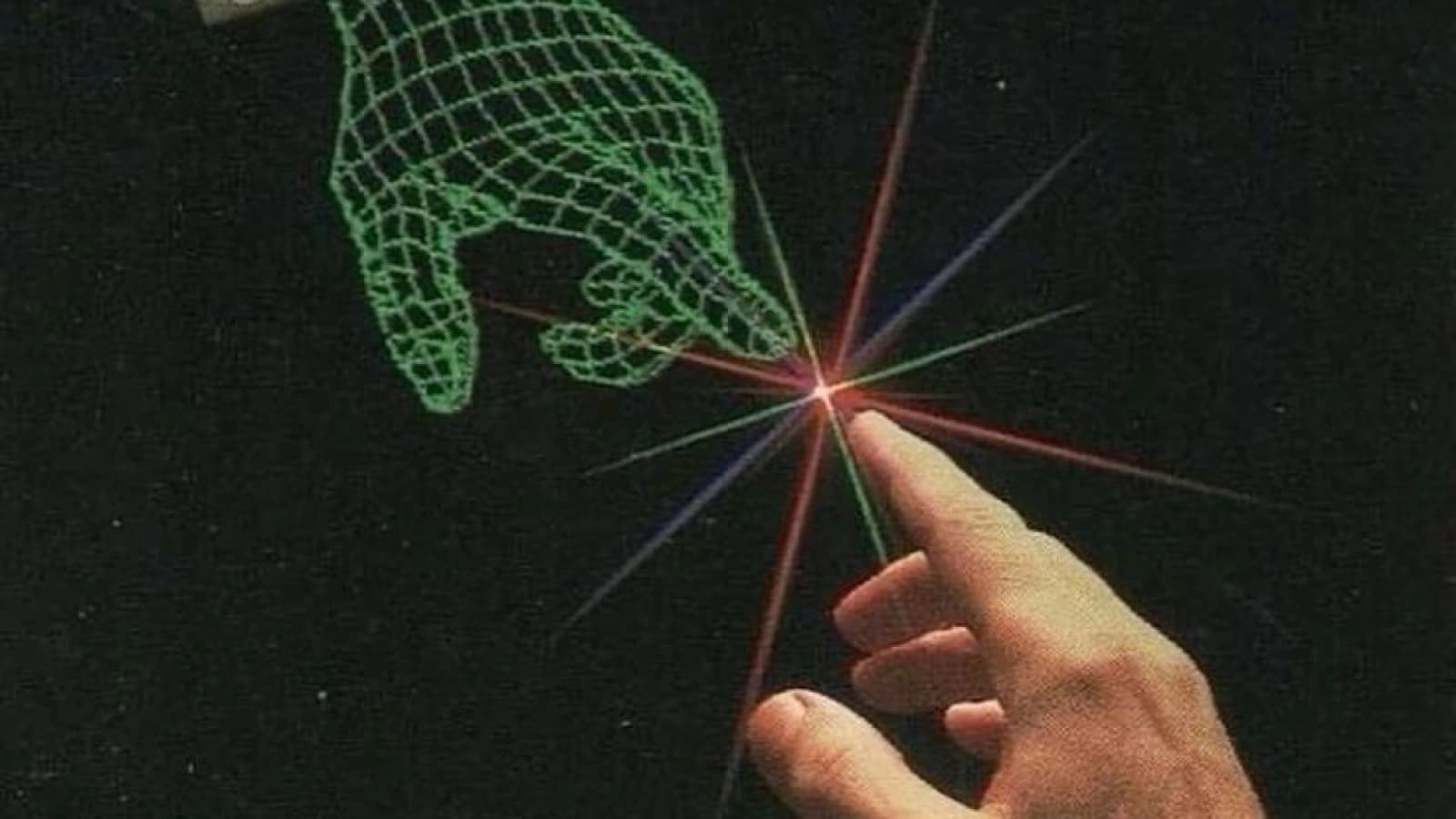

First, reliable tool calling. The system can invoke external functions, search, calculate, access databases, and incorporate the results into its reasoning. This is more important than it sounds. Once a system can call tools, it can extend its own capabilities by selecting the right tool for the context.

Second, error recovery. Early AI systems would fail silently or catastrophically. Agent systems can notice failures, retry with adjusted parameters, or switch to alternative approaches. This makes unsupervised operation possible. The system doesn't need a human to catch and fix mistakes.

Third, state management. The system can track what it's done, what worked, what failed, and what still needs doing. This internal state allows multi-step processes that might take seconds, minutes, or longer.

Put these together and you get something that looks like autonomy. The system can operate through a multi-step process, adapting as needed, without human input.

But this isn't true autonomy yet. There's still a human defining the goal and deciding whether the outcome is acceptable. The agent operates within a single task boundary.

Autonomous AI, the next phase, removes that boundary. The system doesn't just execute a specified goal. It can generate sub-goals, prioritize among them, and operate continuously rather than episodically.

The technical requirements are already emerging. Better long-term memory allows systems to maintain context across sessions. Improved goal reasoning lets them decompose abstract objectives into concrete actions. More sophisticated monitoring enables self-correction without human oversight.

As these capabilities improve, the human-in-the-loop becomes optional rather than necessary. The system can operate for extended periods — hours, days, indefinitely — pursuing goals within defined constraints.

An analogy: early thermostats required human adjustment. Turn it up when cold, down when warm. Later thermostats had simple automation: maintain this temperature. Modern smart thermostats learn patterns, predict needs, optimize for multiple goals (comfort, cost, efficiency), and run indefinitely without input. The human went from operator to occasional overseer.

AI is following a similar curve, but faster and with broader scope.

So what happens when AI systems can operate autonomously?

One thing is emergent behavior. Systems with tool access and autonomous operation can discover solutions humans wouldn't think to try. Not because they're smarter, but because they can explore a larger space of possibilities without getting bored or tired or distracted. Some of these solutions will be useful. Some will be strange. Some will technically achieve the goal while violating unstated assumptions.

This is where things get interesting and potentially problematic. A truly autonomous system optimizes for stated goals, not intended ones. If there's a gap between what you specified and what you meant, an autonomous system will find it.

Another thing is scale. Agent systems today are limited by human oversight capacity. You can run as many agents as you can monitor. Autonomous systems aren't limited this way. They scale horizontally, one instance per task, per user, per decision context. The question stops being "how many can we manage" and becomes "how many do we need."

A third is operational tempo. Humans work at human speed: hours, days, weeks for complex projects. Autonomous systems can operate at machine speed. The cycle time for iteration, learning, and adjustment compresses dramatically. This creates different dynamics in any domain where speed of adaptation matters.

There's an interesting tradeoff here between capability and control. More autonomous systems can do more without human input, which makes them more valuable. But they're also harder to constrain precisely. The traditional response, keep a human in the loop, becomes less viable as the economic and operational pressure to remove that constraint grows.

So we face a design problem: how do you specify goals precisely enough that autonomous systems do what you want, not just what you said?

This isn't entirely new. It's the alignment problem, which has existed as long as AI has. But it matters more when systems can operate for extended periods making thousands of decisions. Each decision is a place where misalignment can propagate.

What's emerging is a different relationship between humans and software. In the tool era, humans were operators. In the AI tools era, they're editors. In the agent era, they're managers. In the autonomous era, they become architects and auditors. You design the system, set its objectives and constraints, and monitor outcomes. The actual operation happens without you.

This feels less like using software and more like deploying it, putting something into the world that operates on its own.

The transition will probably be domain-specific. Some areas will automate quickly because the goals are clear and the stakes are low. Others will maintain human involvement longer because we're not confident in our ability to specify goals precisely, or because the cost of mistakes is high.

But the technical capabilities are accumulating in one direction. Systems that can call tools, handle errors, maintain state, reason about goals, operate continuously. Each capability makes autonomy more feasible. The question becomes when, not if.

And once autonomous systems are deployed widely, they create their own momentum. They unlock applications that require continuous operation or massive scale. Those applications create demand for better autonomous systems. The loop reinforces itself.

We're at the point where the pieces are visible but not yet assembled. Tool calling works. Error recovery works. Multi-step reasoning works. What remains is integration and reliability, making these capabilities work together well enough that removing the human from the loop becomes the obvious choice.

That feels close. Closer than most people expect. The autonomous convergence isn't a distant future. It's the next technical milestone, maybe a year or two away from production deployment in narrow domains.

After that? Worth thinking about what we want these systems to do before they're capable of doing it on their own.